The Diponegoro War

1825 - 1830

Duncan MacDonald

Jakarta 4 July 2011

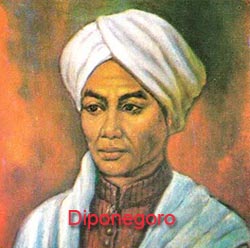

How did this man who came from a life of privilege in the Yogyakarta court - he was the grandson of Yogyakarta's first sultan - end his life in exile in squalid, hot, prison rooms at Fort Rotterdam in Makassar.

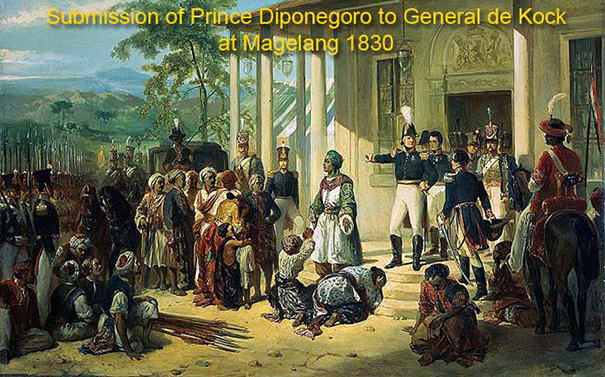

painting by Nicholaas Pieneman

Background

The second Mataram kingdom emerged from Demak, the most powerful early Muslim kingdom on Java. Military conquests during the long reign of Sultan Agung Hanyokrokusumo, from 1613 to 1646, greatly expanded and set in place the lasting historical legacy of Mataram.In 1677, King Amangkurat II sought the assistance of the Dutch East India Company (VOC) in reclaiming his throne which had been usurped by his brother - BIG MISTAKE. As a consequence he had to make substantial concessions to the Dutch, resulting in seventy five years of political and military conspiracies, chicanery and collusion between various Javanese princes, Chinese entrepreneurs, and the Dutch, who all sought to establish their own trading empires in Java.

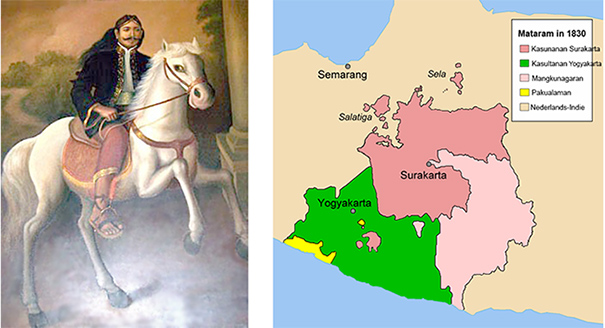

A land dispute between two brothers in 1755, the Sultan of Surakarta (present day Solo), and his brother Prince Mangkubumi led to the founding of Yogyakarta. This was the result of the Treaty of Giyanti signed on 13 February 1755 in which the Mataram Sultanate was split in two; the Surakarta Sultanate and the Yogyakarta Sultanate.

Prince Mangkubumi known as Sultan Hamengkubuwono I, became the 1st Sultan of Yogyakarta

Prince Mangkubumi known as Sultan Hamengkubuwono I, became the 1st Sultan of Yogyakarta

Mangkubumi left Solo in a temper tantrum after presumably loosing the argument. He returned to Yogyakarta to build the walled palace called the Kraton. He took the title of Sampeyan Dalem Ingkang Sinuwun Kanjeng Sultan Hamengkubuwono Senopati Ingalaga Abdul Rakhman Sayidin Khalifatullah Panatagama (His Majesty, The Sultan-Carrier of the Universe, Chief Warrior, Servant of the Most Gracious, Cleric and Caliph that Safeguards the Religion).

The old adage of "give them money or status" was aparently alive and well, even in those days. We can assume Mangkubumi was left with only status.

Prince Diponegoro was a grandson of Yogyakarta’s first sultan, Mangkubumi. Diponegoro was also a nephew of Sultan Hamengkubuwono II, whom Napoleon's appointed Governor-General W.H. Daendels pushed aside in 1810 and whom Britain's Lieutenant General T.S. Raffles forced to abdicate in 1812 after bombarding then storming the Yogyakarta palace.

He was the eldest son of the prince, whom Raffles chose to be Hamengkubuwono III (ruled 1812-1814). Diponegoro was also the half-brother to the ten-year-old boy Raffles subsequently installed as Hamengkubuwono IV (ruled 1814-1822).

Sultan shuffling

The Dutch put Diponegoro’s five-year-old nephew on the throne in 1822 and appointed Diponegoro as one of the three advisors for the boy called Hamengkubuwono V. In 1826 the Dutch brought back Diponegoro’s uncle from exile, but in 1828 Hamengkubuwono II was deposed for the final time. Hamengkubuwono V continued his reign as sultan until his death in 1855. Diponegoro’s desire to become sultan was thwarted to a great extent by the British and the Dutch. Prince Diponegoro Sultan Hamengkubuwono II Sultan Hamengkubuwono V

Prince Diponegoro Sultan Hamengkubuwono II Sultan Hamengkubuwono V

Diponegoro’s ambition was also frustrated by Javanese tradition on succession. His claim to succeed was based on his father and grandfather. But there was no supporting royal ancestry or rank on his mother’s side. She had only been a minor temporary wife, (R.A. Mangkarawati from Pacitan), of Hamengkubuwono III. Diponegoro passed into the care of a queen who lost her importance in the palace when Hamengkubuwono I died. She took Diponegoro with her when she was permitted to leave the palace for the pesantren of Tegalreja, a pilgrimage site and centre for the study of Javanese Islamic literature.

Diponegoro grew up as a prince with income from his own tax lands but outside the palace. His perspective on the royal capital and understanding of its politics were formed in an Islamic mini-state, a thriving environment of artisan workshops, trade and rice lands where there were no royal tollgates and no Chinese leaseholders collecting the Sultan’s taxes. His early years covered a period of growing prosperity for Yogyakarta’s farmers. No royal surveys were made of cultivated land between 1755 and 1812, leaving many farmers free to raise rice, tobacco, indigo, peanuts and cotton for sale without paying taxes.

Farmers problems

Diponegoro became familiar with the problems and perspectives of farmers because, unlike his royal relatives who never left the capital, he visited his territories. He also built up a following in the pesantrens and through his pilgrimages to holy sites in central Java.Diponegoro’s travels allowed him to learn of changing political and economic conditions and how the peasants viewed them. He witnessed the harmful effects of his uncle’s reign, the heavy burdens on farmers and artisans for his building projects, his increased taxes in 1812 and his extensive dealings with Chinese entrepreneurs.

Tollgates & gangs

Tollgates proliferated between 1816 and 1824 and marauding gangs multiplied in the countryside. Yogyakarta’s sultan and princes leased land and labourers to Chinese and Europeans, who organised their workers for growing export crops. The seat of Java’s sacred kings were controlled by non-Muslims. Diponegoro saw the reduction of royal territory as British and then Dutch officials took control of large slices of Java. A reduced base of tax payers had to support an increasing number of royal retainers, officials, favourites and relatives. By 1820 a prosperous farming society was being reduced to poverty.

who organised their workers for growing export crops. The seat of Java’s sacred kings were controlled by non-Muslims. Diponegoro saw the reduction of royal territory as British and then Dutch officials took control of large slices of Java. A reduced base of tax payers had to support an increasing number of royal retainers, officials, favourites and relatives. By 1820 a prosperous farming society was being reduced to poverty.When Raffles placed Hamengkubuwono IV on the throne, the Sultan chose as partners four women who had been concubines of his father, uncle and grandfather. This greatly upset the women's relatives, religious leaders and factions in the palace. Javanese custom frowned on the circulation of women between kin and generations, as they believed it likely to bring ill-fortune to the reign. Also marriage with a father's wives was prohibited in the Koran.

More proof of the palace's declining morality was the wedding ceremony of Hamengkubuwono IV to one of his wives. The royal bridegroom entered the mosque on the arm of the non-Muslim John Crawfurd, Britain's representative to the Yogyakarta court. Condoning this intrusion of Muslim space were royal male relatives, the chief mosque official, ulamas and pilgrims returned from Mecca.

Diponegoro also believed Yogyakarta's sultans favoured the Chinese entrepreneurs and gave them prominence and power over the Javanese.

Visions

The Goddess

of the Southern Ocean came as a vision to Diponegoro

The Goddess

of the Southern Ocean came as a vision to Diponegoro

Diponegoro underwent a religious experience and a series of visions in 1808 which convinced him that he was the divinely appointed future king of Java. The Goddess of the Southern Ocean came to him and promised him her aid, thereby confirming his status as a future king. A disembodied voice finally made it known he was to initiate a period of devastation which would purify the land. (These revelations were contained in writings Diponegoro made while in captivity in Fort Rotterdam).

PART TWO

The population of Java had increased significantly in the fifty years of peace that had followed the Treaty of Giyanti. It was now facing a critical problem of food supply. Yogyakarta in the early 1820's was experiencing a string of natural disasters. Drought and poor harvests in 1821 and 1825 exacerbated the problem. However farmers were increasingly obliged to pay their government taxes in money rather than kind. As a result they were forced into the hands of the moneylenders, who were for the main part Chinese.

exacerbated the problem. However farmers were increasingly obliged to pay their government taxes in money rather than kind. As a result they were forced into the hands of the moneylenders, who were for the main part Chinese.In 1821 a cholera epidemic struck. To cap it all, the volcano Mt Merapi, just to the north of Yogyakarta erupted in 1822. These disaster combined to convince many that the Sultan was losing his right to rule and that there would soon emerge a new sultan. Sultan Hamengkubuwono IV died in 1822, amid rumours that he had been poisoned and there were heated arguments over the appointment of guardians for his three year old son, Hamengkubuwono V.

Diponegoro, from outside the palace, encouraged the view that he was the Just Prince, come to take the throne and free his people from oppression and return the kingdom to a state of harmony and tranquillity.

If Diponegoro was increasingly seen as an ally by those Javanese opposed to the rulers of Yogyakarta, conversely he was seen as a threat by both those rulers and the Dutch.

Something had to be done to bring him to heel. A decision was made to drive a road through his rice fields in Tegalrejo. This led to armed resistance and an excuse for a Dutch-Javanese force from Yogyakarta to be despatched on 20 July 1825 to Tegalrejo to capture Diponegoro. Tegalrejo was captured and burned but Diponegoro escaped and raised the banner of rebellion, thus sparking the Diponegoro War.

Diponegoro's explosive revolt

Diponegoro was forty years old when he exploded out of his private lands in revolt against Hamengkubuwono V and his Javanese and Dutch backers. The rebel prince's opposition appealed to the newly poor , to the religiously committed and to many royal factions. Diponegoro promised righteous rule and justice in taxation. To religious circles he denounced the submission of Muslims to non-Muslim tax-collectors, landlords and agents of government. He held in contempt the palace faction that allowed non-Muslims to depose and install Java's sultans. He preached hatred of European and Chinese for their refusal to embrace Islam, their prosperity from taxing and selling opium to Muslims, their foreign clothes, diet and habits. To alienated palace staff he offered himself as sultan.However Diponegoro was no revolutionary. He stood for monarchy and inherited privilege. He had no intellectual interest in ideas outside the traditions of Javanese Islamic mysticism.

Of the twenty-nine princes in Yogyakarta, fifteen initially joined Diponegoro. As did forty-one of eighty-eight bupatis (senior palace officials). They bought armed retainers and bodyguards with them. The religious hierarchy of the palace and residents of tax-free villages joined. The religious community rallied behind Diponegoro, among them Kyai Maja, who became the spiritual leader of the rebellion. A band of one hundred and eight kiais, thirty-one hajis, fifteen ulamas, twelve religious officials and four teachers brought men armed with pikes, spears and krises.

The uprising was centred in Diponegoro's home region of south-central Java. Related uprisings occurred in areas stretching from Tegal, Rembang and Madiun to Pacitan.

The princes of Madura and most regional Javanese officials opposed the rebel cause.

Blockade the palace

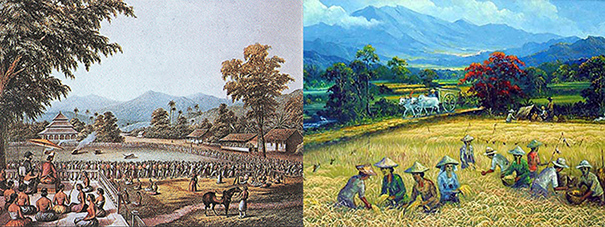

19th century - Yogyakarta Palace Yogyakarta rural scene

19th century - Yogyakarta Palace Yogyakarta rural scene Diponegoro's strategy against Hamengkubuwono V was to blockade the palace and stop the collection of income and food. Armed gangs who joined his cause attacked the residences and workshops of Europeans and Chinese, but not the royal capital. Massacres using axes, knives and spears sent survivors fleeing the countryside to the towns and cities. Diponegoro pressured farmers not to sell their produce in Yogyakarta.

The war was a series of provincial uprisings, loosely coordinated by Diponegoro and his advisors who stayed mainly in the old Mataram heartland. They communicated to other rebel groups in central and north Java by letter. Men joined and deserted depending on the ebb and flow of battle and on Diponegoro's personal leadership.

Diponegoro's jihad

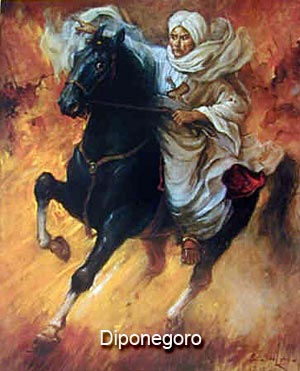

Diponegoro stressed the Muslim character of the war by calling it a jihad. He looked to the Ottoman emperor, as head of the Islamic world, for support. He rode into battle dressed in what was thought of in Java, as a Turkish costume: trousers, jacket and turban. With the genes of his grandfather running through him, Diponegoro assumed a similar string of titles including; First Among Believers, Lord of the Faith, Regulator of the Faith in Java, Sultan, and Caliph of the Prophet of God. He also adopted older titles such as Erucakra, meaning "Emergent Buddha".For the first two years of rebellion, Diponegoro's armies were very successful. He used the landless and the itinerant as soldiers, porters and guards of mountain strongholds. He could incite farmers and peasants to attack passing columns of Javanese and Dutch soldiers.

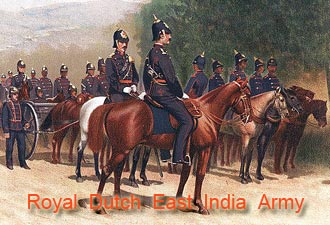

Dutch troop strength by 1826 were adequate, but poorly led. Large formations of government forces achieved little against the rebel's mobile guerrilla tactics.

Diponegoro suffered a major setback when he was defeated in front of Surakarta. Nevertheless by the end of 1826, government forces seemed at a standstill and Diponegoro controlled much of the countryside of central Java.

In August 1826 the Dutch brought back aging Sultan Hamengkubuwono II from exile in Ambon and reinstated him on the throne at Yogyakarta (1826-28). This transparent ploy failed to win any Javanese support away from the rebels.

Loosing battles

By 1827 however, Diponegoro's men began losing battles. The Dutch were learning how best to use their troops. They adopted the benteng-stelsel (fortress system) where small mobile columns operated independently from an ever-growing network of strategic fortified posts and permanently policed the local population. Cholera, malaria and dysentery claimed many on both sides.

losing battles. The Dutch were learning how best to use their troops. They adopted the benteng-stelsel (fortress system) where small mobile columns operated independently from an ever-growing network of strategic fortified posts and permanently policed the local population. Cholera, malaria and dysentery claimed many on both sides. Chinese suppliers refused to sell ammunition to the rebels after Diponegoro's followers massacred families of Chinese including Muslim Chinese.

Desertions and captures from the rebel side increased. In November 1928 Kyai Maja surrendered to the

Dutch along with many other Islamic leaders, when Diponegoro declared himself Imam, Regulator of Islamic Life and set himself over Islamic scholars.

Dutch along with many other Islamic leaders, when Diponegoro declared himself Imam, Regulator of Islamic Life and set himself over Islamic scholars.Princes quickly changed sides as the Dutch gained control of the countryside.

Surrender of key allies

In September 1829 Diponegoro's uncle Pangeran Mangkubumi surrendered and was allowed to return to Yogyakarta. Ali Basa Prawiradirja, known as Sentot also surrendered. Sentot was given the rank of Lieutenant Colonel in the colonial army and went to West Sumatra to fight on the Dutch side against the Padris.Arrested

Finally on 28 March 1830 Diponegoro entered into negotiations in Magelang. His personal following was reduced to a few hundred retainers, slave women, minor wives and servants. What he expected to come of this meeting is unclear, but it was inevitable that he would be arrested by the Dutch.

The Dutch at the time felt the capture of Diponegoro to be an important event in the history of Java. General H.M. de Kock, who led the Dutch forces and engineered the arrest of Diponegoro, commissioned the artist Nicolaas Pieneman (1809-1860) to preserve the nadir of Diponegoro in a large painting {see first painting}. Diponegorohad presented himself for negotiations with de Kock in Magelang as a prince of Islam, rather than as heir of royal Java. In the painting Javanese male followers surround their imam and women kneel, The Dutch flag flies over the house of Holland's representative. Lances surrendered by Diponegoro's retainers lie on the foreground. At the top of the steps stands de Kock pointing to the coach that will take Diponegoro into exile.

Diponegoro was taken first to Manado then in July 1833 moved to Makassar, where he was confined in rooms in Fort Rotterdam.

Visit by Dutch prince

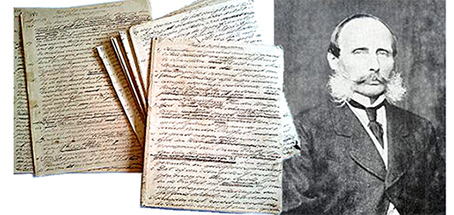

Autobiographical Chronicle of Prince Diponegoro Prince Henry of the Netherlands

Some Dutch intelligentsia were impressed by the mystique that surrounded Diponegoro. Prince Henry, the sixteen-year-old son of the future William II of the Netherlands, visited him in his Fort Rotterdam prison in 1837. Henry wrote his father to describe a man who, in miserable, hot quarters, spent his time copying the Koran and drawing, met him with a pretended cheerfulness. "He has a pleasant appearance and one senses he is still full of fire." recorded the Prince. He thought the arrest of Diponegoro was a stain on Dutch honour. However nothing was done to release him from his small rooms or alleviate his discomfort.

The Babad Diponegoro (The Chonicle of Diponegoro) written in Manado in 1831-32, is regarded as the first autobiography in modern Javanese literature. The original manuscript is considerted lost, but a 19th century copy of the original, in Javanese with Arabic letters, is kept in the National Library of Indonesia. An early translation into Dutch is kept by KITLV (an institute of the Royal Nethherlands Accadamy of Arts and Sciences).

The chronicle was incribed in the UNESCO Memory of the World Register in 2013.

Diponegoro died in Fort Rotterdam in 1855. His tomb, alongside his wife who by strange coincidence also died in 1855, remains a place of pilgrimage.

The Diponegoro war cost the lives of 8,000 Europeans and 7,000 Indonesian soldiers. Some estimates put the number of Javanese deaths from illness or starvation at 200,000. Few were direct casualties of battle. The population of Yogyakarta was reduced by half.

Conclusion

Diponegoro lived long enough to see Chinese regain control of trade and manufacturing in Java and to see the forging of a powerful alliance between Javanese aristocrats and the Dutch to tax Java's farmers.Javanese district officials who owed their jobs to the Dutch, focused their energies on making their jobs heritable by their sons.

They propagated the idea that they were the natural leaders of the Javanese, that sacred ties bound them to the people and only through them could the Dutch rule. For many years thereafter Dutch governance would be based on an alliance with the indigenous aristocracy.

While the aristocracy could be seen to have won the battle, in effect they had lost the war. The aristocracy had lost its last chance for self-determination.

This would remain the fact until full independence was gained for Indonesian citizens, over one hundred years later

in the late 1940's.

Statue of Diponegoro, Jakarta Tomb of Diponegoro and his wife at Fort Rotterdam, Makassar

Statue of Diponegoro, Jakarta Tomb of Diponegoro and his wife at Fort Rotterdam, Makassar

This Digest article can be downloaded as a FREE e-book on Smashwords.

Available on iPad / iBooks, Kindle, Nook, Sony, & most e-reading apps including Stanza & Aldiko.

Just click the following link

>> download free e-book dMAC Digest Vol 4 No 4