Duncan MacDonald

Jakarta 20 April 2015

What is Meningitis ?  Meningitis is a disease caused by the inflamation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord known as the meninges (men-in-jeez).

Meningitis is a disease caused by the inflamation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord known as the meninges (men-in-jeez).

Meningitis comes in different forms;

• Bacterial Meningitis is an extremely serious illness requires immediate medical care. If not treated quickly it can cause death within hours – or lead to permanent damage to the brain and other parts of the body.

Bacterial meningitis is caused by any of several bacteria. Neisseria meningitidis or ‘meningococcus’ (muh-ning-goh-KOK-us) is common in children and young adults. Streptococcus pneumoniae or ‘pneumococcus’ is another common cause in children and adults. Haemophilus influenzae type B (Hib) was a common cause of meningitis in infants and young children until the Hib vaccine was introduced for infants.

Meningococcus and pneumococcus account for most of the bacterial meningitis cases in the U.S. and UK. Vaccines are available for both Meningococcus and Pneumococcus. They are recommended for all children and adults at special risk.

The bacteria can be spread among people in close contact through the exchange of respiratory and throat secretions (spittle – saliva or spit), particularly in places such as schools and colleges, by coughing, sneezing and kissing.

If you are around someone who has bacterial meningitis, contact your health care provider to ask what steps you should take to avoid infection.

In many instances bacterial meningitis develops when bacteria gets into the bloodstream from the sinuses, ears or other part of the upper respiratory tract. The bacteria then travels through the bloodstream to the brain.

Bacterial meningitis is most common during the winter months.

• Viral Meningitis is more common than the bacterial form and generally – but not always – less serious. It can be triggered by a number of viruses such as Enteroviruses, Arboviruses and Herpes simplex viruses, including several that can cause diarrhea, chickenpox and mumps. Viral meningitis is most commonly spread through fecal contamination.

While generally less severe than bacterial meningitis, people with normal immune systems usually get better on their own. There are vaccines to prevent some kinds of viral meningitis.

People with viral meningitis are much less likely to have permanent brain damage after the infection resolves. Most will recover completely.

• Fungal Meningitis is much less common than the other infectious forms. It is caused by fungi such as Cryptococcus and Histoplasma usually by inhaling the fungal spores from the environment. People with certain medical conditions such as diabetes, cancer or HIV are at higher risk of fungal meningitis.

• Parasitic Meningitis is caused by parasites and is less common in developed countries. Parasites, like Angiostrongylus cantonensis, can contaminate food, water and soil.

• Non-Infectious Meningitis is not spread from person to person, but instead caused by cancers, systemic lupus erythematosus (lupus), certain drugs, head injury, and brain surgery.

Who are Most at Risk from Meningitis?

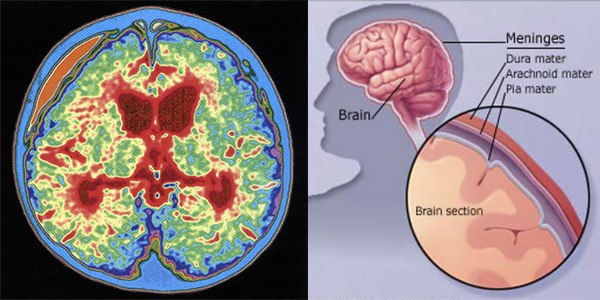

Abscess due to Meningitis: This color-enhanced MRI scan (left) of a baby’s brain shows a large abscess (pale orange at the upper left of the image) between the dura matter and the arachnoid that has formed as a result of infection of the meninges.

Anyone can develop just about any kind of meningitis. But research has shown that some age groups have higher rates of meningitis than others. They are:

◊ Children under age 5

◊ Teenagers and young adults age 16-25

◊ Adults over age 55

Studies have shown that meningitis is more of a danger for people with certain medical conditions, such as a damaged or missing spleen, chronic disease or immune system disorders.

Because certain germs that cause meningitis can be contagious, outbreaks are most likely to occur in places where people are living in close quarters. So college students in dorms or army recruits in barracks are at a higher risk. So are people travelling to areas where meningitis is more common, such as parts of Africa and participants in the annual Hajj pilgrimage.

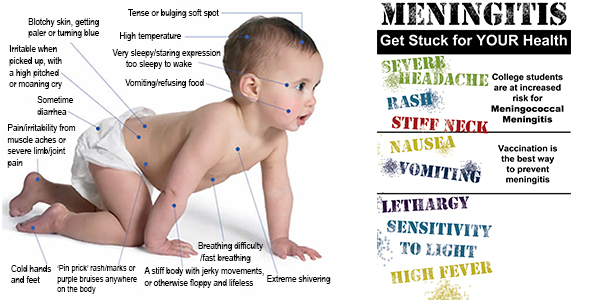

What are the Symptoms?

Initially, meningitis may produce vague flu-like symptoms, such as mild fever and pains. More pronounced symptoms may then develop. Symptoms are the most severe in bacterial meningitis and may develop rapidly, often within a few hours.

The symptoms of viral meningitis may take a few days to develop, while fungal meningitis symptoms develop slowly and may take several weeks to become pronounced.

In adults the main symptoms of meningitis may include the following:

◊ Severe headache

◊ Fever

◊ Stiff neck

◊ Sensitive to bright light

◊ Nausea and vomiting

◊ Confusion or difficulty concentrating

◊ Lack of interest in drinking and eating

Unless prompt treatment is given the bacterial meningitis may lead to drowsiness, seizures and coma. In some cases pus collects, which results in compression of nearby brain tissue.

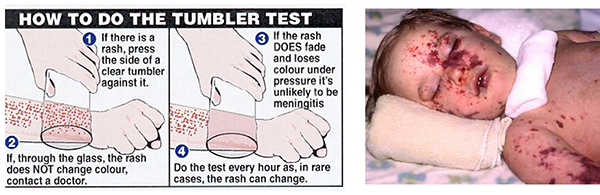

Meningococcal Rash

In meningococcal meningitis, a rash of flat dark red or purple spots may appear that develop into blotches. The rash does not fade when pressed and viewed under a glass.

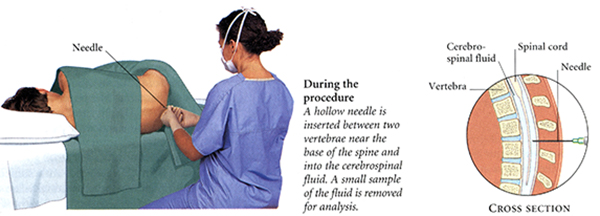

If meningitis is suspected, immediate medical attention and admission to a hospital is necessary. Intravenous antibiotics are started immediately. A sample of fluid from around the spinal cord is then taken and tested for evidence of infection (Lumber puncture), CT scanning, or MRI may be carried out to look for a brain abscess.

Lumber Puncture

Lumber puncture

A lumber puncture is done by positioning a person, usually lying on one side, applying local anesthetic, and inserting a needle into the dural sac (a sac around the spinal cord) to collect cerebrospinal fluid (CSF). When this has been achieved, the ‘opening pressure’ of the CSF is measured using a manometer.

Bacterial meningitis: If confirmed by the lumber puncture test, antibiotics are continued for at least a week. If meningitis is found to be caused by tuberculosis bacteria, anti-tuberculosis drugs will be given. In the case of bacterial meningitis, continuous monitoring in an intensive care unit is often required. Intravenous fluids, anticonvulsant drugs, and drugs to reduce inflammation in the brain, such as corticosteroids, may be given.

Viral meningitis: is more common than the bacterial form. There is no specific treatment for viral meningitis. As long as bacterial meningitis has been excluded by tests, people with viral meningitis are usually allowed to go home if they are well enough. They may be given drugs to relieve symptoms, such as painkillers for headaches.

Fungal meningitis: is treated with intravenous antifungal drugs in hospital. Fungus-related meningitis is rare in healthy people. However anyone who has an impaired immune system, such as a person with AIDS is more likely to become infected with this form of meningitis.

Immunization

Meningococcus vaccines exist against groups A, C, W135 and Y. In countries where the vaccine for meningococcus group C was introduced, cases caused by this pathogen have decreased substantially. A quadrivalent vaccine now exists, which combines all four vaccines. Immunization with the ACW135Y vaccine against four strains, is now a visa requirement for taking part in the Hajj.

• Children should be immunized against Haemophilus influenza type B (Hib) and Neisseria meningitis type C.

• Teenagers should be immunized against Neisseria meningitis type C, unless they have been immunized previously.

• People travelling to high-risk areas such as Africa or Saudi Arabia should be immunized.

• No vaccine is yet available against type B meningococcal meningitis.

Pneumococcal Vaccine: What You Need to Know

1) Why get vaccinated?

Infection with Streptococcus pneumoniae bacteria can cause serious illness and death. Invasive pneumococcal disease is responsible for about 200 deaths each year among children under 5 years old and is the leading cause of bacterial meningitis in the United States.

Children under 2 years of age are at the highest risk for serious disease.

Pneumococcus bacteria is spread from person to person through close contact. Pneumococcal infections can be hard to treat because the bacteria have become resistant to some of the drugs that have been used to treat them. This makes prevention of pneumococcal infections even more important.Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine can help prevent serious pneumococcal disease, such as meningitis and blood infections. It can also prevent some ear infections. However ear infections have many causes, and pneumococcal vaccine is effective against only some of them.

2) Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is approved for infants and toddlers. Children who are vaccinated when they are infants will be protected when they are at greatest risk for serious disease.

Some older children and adults may get a different vaccine called pneumococcal polysaccharide vaccine.3) Who should get the vaccine and when?

Children under 2 years of age:

• 2 months

• 4 months

• 6 months

• 12 to 15 months

Children who were not vaccinated at these ages can still get the vaccine. The number of doses needed depends on the child’s age. Ask your health care provider for details.

Children between 2 and 5 years of age:

Pneumococcal conjugate vaccine is also recommended for children between 2 and 5 years old who have not received the vaccine and are at high risk of serious pneumococcal disease. This includes children who:

• have sickle cell disease

• have a damages spleen or no spleen

• have HIV/AIDS

• have other diseases that affect the immune system, such as diabetes, cancer, or liver disease

• take medications that affect the immune system, such as chemotherapy or steroids

• have chronic heart or lung disease

• attend group day care

4) Some children should not get pneumococcal conjugate vaccine or should wait, if they have a severe (life-threatening) allergic reaction to a previous dose of this vaccine. Children with minor illnesses, such as a cold, may be vaccinated. However children who are moderately or severely ill should wait until they recover before getting the vaccine.

5) What are the risks from pneumococcal conjugate vaccine?

In studies (nearly 60,000 doses) pneumococcal conjugate vaccine was associated with only mild reactions:

• Up to about 1 infant out of 4 had redness, tenderness, or swelling where the shot was given.

• Up to about 1 out of 3 had a fever of over 38 Celsius (100.4 Fahrenheit), and up to about 1 in 50 had a higher fever, over 39 C (102.2 F).

• Some children also became fuzzy or drowsy, or had a loss of appetite.

So far, no moderate or severe reactions have been associated with this vaccine. However, a vaccine, like any medicine, could cause a severe allergic reaction. www.CDC.gov/vaccines

Meningitis in Children

Bacterial meningitis is a potentially fatal condition and causes between 150 and 200 deaths each year in the UK. About eight in 10 cases of bacterial meningitis occur in children under the age of five. Outbreaks of the infection can occur in communities where children are in close contact with one another, such as nurseries and schools.

Children with viral meningitis usually recover fully in about two weeks. Bacterial meningitis proves fatal in about one in 20 cases. About one in four children who recover, have long term problems such as impaired hearing or epilepsy.

Mortality from meningitis was very high (over 90%) in early reports. Bacterial meningitis occurs in about 3 people per 100,000 annually in Western countries. In Brazil, the rate is higher at 45.8 per 100,000 annually.

Sub-Sahara Africa has been plagued by large epidemics of meningococcal meningitis for over a century, leading it to be labeled the ‘meningitis belt ’. Epidemics typically occur during the dry season (December to June) and an epidemic wave can last two to three years, dying out during the intervening rainy seasons. Attack rates of 100-800 cases per 100,000 are encountered in this area, which is poorly served by medical care. The largest epidemic in recorded history swept this area in 1996-1997, causing over 250,000 cases and 25,000 deaths.

The African meningococcal meningitis belt

The African meningococcal meningitis belt

In 1944, penicillin was first reported to be effective in the treatment of meningitis. The introduction in the late 20th century of Haemophilus vaccines led to a marked fall in cases of meningitis associated with this infectious agent.

In 2002, evidence emerged that treatment with steroids could improve the likely outcome of bacterial meningitis.

Viral meningitis may improve without treatment, but bacterial meningitis is serious, can come on very quickly and requires prompt antibiotic treatment. Delaying treatment for bacterial meningitis increases the risk of permanent brain damage or death.

In addition, bacterial meningitis can prove fatal in a matter of days.

There is no way to know what kind of meningitis you or your child has, without seeing your doctor and undergoing spinal fluid testing.

It is also important to talk to your doctor if a family member or someone you work with has meningitis. You may need to take medications to prevent an infection.

* * * * *

That's Life

This Digest article can be downloaded as a FREE e-book on Smashwords.

Available on iPad / iBooks, Kindle, Nook, Sony, & most e-reading apps including Stanza & Aldiko.

Just click the following link

>> download free e-book dMAC Digest Vol 5 No 2